Note to readers: this poem is best viewed on a full-screen device or in mobile desktop mode.

A Particle Theory of Inheritance by Gabrielle Langley

—for my father, the physicist

A stranger died in my childhood home

before we lived there. We knew this

because a long fluid shadow, a human-shaped stain

marked the wooden floor where he fell.

Our father never spoke of the dead man.

But he told other stories, and whenever he spoke

secret stars would fly from his mouth.

A ruby on Jupiter. Diamonds on Neptune.

Neutrinos. Nebulae. Gluons and galaxies.

We would never learn the dead man’s name,

but astronomy and physics taught us

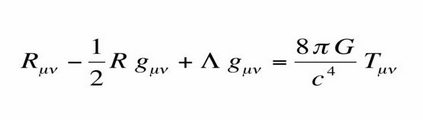

Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity:

which told us the dead man’s mass

was able to bend space. And with E = mc2

we could be pretty sure, he became the waves.

Children learn to read and cipher in rooms

like this, learn to crisscross the silvered lines

of comets and ghosts, learn how the dust

from exploded stars can be used for polishing.

Old houses are always haunted behind the shiplap.

Our ancestors sing in the quarter-sawn oak.

The particles of our dead dance, always in circles.

They dance through the straight edges of sanded wood.

These are the floors we walk, the bare walls of a house

papered over with poems. The boundaries

are not boundaries. Indelible marks

wherever we fall, we are also the stars, rising.