After The Labyrinth by Cynthia June Long

Theseus, son of Aegeus, hero of Athens,

tunic dyed red by the blood of the beast,

turns a final corner, emerges into night.

Twenty-four lost youths stumble behind him.

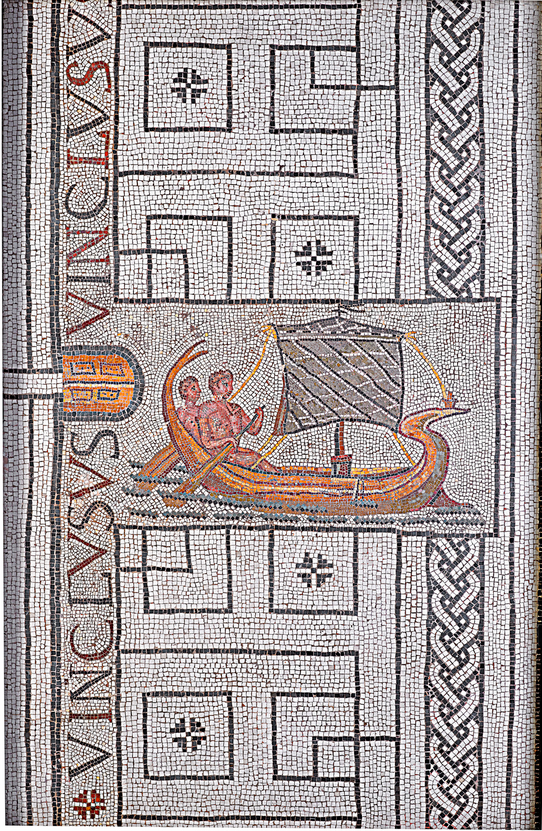

His seaman’s hands,

roughened by hauling line, calloused from sewing canvas,

toughened at the oars of his father’s best trireme,

hand over hand followed Ariadne’s clew to freedom.

Such a narrow thread, no weighty sailor’s hemp, this—

light-weight flax like gossamer,

thin like the single horse-hair which upheld Damocles’ sword—

This homespun yarn brought freedom.

Ariadne begs. “Take me with you

before my father unravels your success.”

He lifts her over the gunwale.

A battering wind catches the sails, pulls them from shore.

She tries to kiss him while he sights upon the stars.

The youths doze on the deck, famished and weak.

Seasickness fills the ocean, is washed by sloppy waves.

From his depths Poseidon follows, and Dionysus above notes their progress.

“Let us wager.” Struck by her beauty, the Drunkard challenges the Sea Lord.

“Which of us shall claim this princess of Crete? No fighting, now. Leave it to luck.”

Bouncing a silver coin of Knossos in his wine-stained hand,

the grape-god tosses it into the sky. The coin like a full moon rises.

“Heads,” he calls, and, “labyrinth.”

It falls back to his palm, blazing like a falling star, and the God of Grapes

flips it onto his forearm to display the wandering passages. Thus he wins his prize.

The ocean churns as Poseidon mourns his loss.

Even Ariadne pulls the oars. Her fair hands blister.

It will be months before she can spin again.

The waves rise and break upon each other, split upon the bow,

shower and scour the wounds of the shivering youths.

Her clew knots in the hold.

Finally they reach Naxos.

They dance, like cranes, retracing the steps of their prison.

Theseus will never be this happy again.

Dionysus demands. Theseus complies. Some hero, he.

He offers Ariadne to comfort the God of Grapes.

(She doesn’t get a choice. Is a god a better lover? A better husband? A better father?)

Her god-gift coronet still shines in the stars, blazing spite.

Theseus is braver than he knows.

His sails foretell

his father’s doom—the blood black sails as dark as midnight

falsely proclaim failure in his quest.

Poseidon gloats. He knows the king will mourn and throw

himself

into the sea

which evermore shall bear Aegeus’ name. A fitting end.

The Sea God always gets his due. He roars with the wind.

Soon Theseus will mourn his father

and take up the mantle of kingship.

Soon he will cross the Aegean

on his way to the great river Styx,

the journey alone from one black night into another.