The Legend of Saint Adstock by Andrew Deathe

1.

Do you know, child, the story of how our village church came to be built here? Why it has thick stone walls, a roof of reed thatch, and why there is a well that flows from the churchyard? Do you know why it is named for a foreign saint, from across the border? Settle down here beside me and listen then, for this is a story of how the Saxons came to our ways and beliefs, after they came to our lands.

Among the nobility of those people was a handsome man who was born to good parents and whom they named Adstock. His father was an earl who held fine lands from King Whaddon. Whaddon and his followers had been on this island for only two generations but they knew no other home, so they called it their own. They fought each other frequently for land, for honour and for pleasure. They were strong warriors, and well-led in battle. Their kingdom stretched as far as the borders of our own country and at times they fought our people too. At that time the Saxons were still pagans but Whaddon’s people fought us not because we worshipped differently but because we had land, and that is all that most kings want, whomsoever they turn to in prayer. Because of that we cannot say that Whaddon was a great king, but we will say that he was a good king.

Adstock was blessed with a good birth, lived a happy childhood and had a privileged adolescence. This was followed by the fortunate existence of a young man of the titled class. He rode horses liveried in scarlet cloth , carried a dagger which was set with crystals and he fastened his cloak with clasps made of gold. His father raised his son to do the things that aristocrats do, so that he could succeed him in time and raise sons of his own to do the same. Adstock made his parents proud and he was proud of himself.

But when he had lived twenty years, Adstock became sullen and withdrawn. Whereas before he was the first among his friends to ride down a hind, now his bridle hung cobwebbed. When the men of the district took up their spears and sought boars in the forest, his blade lay rusting. When couples courted and danced in his parent’s hall, he retreated to the corner and could hardly raise his eyes to them.

His mother and father worried for their son. They talked about him to each other. They talked about him to the thanes of their hall. They talked about him to the other earls in the hall of King Whaddon. They would have talked to the king himself, but the king was too busy doing good deeds, although not good enough for him to be a great king.

Finally, when they had spoken with everyone else and received no advice on the matter, Adstock’s parents talked to their son. They asked what was wrong, why he did not chase hinds, nor boars, nor maidens. They implored their son to speak to them.

His mother said, “Speak, boy, and share with me your sorrow.”

His father said, “Speak, boy, and cast off your sorrow.”

And in time Adstock spoke to them and said “Father, mother, I am hollow inside. I have everything men wish for. I want not for sustenance, nor entertainment, nor goods. My body is fulfilled; my head has all it can imagine. And yet my heart is without spirit; I am incomplete. I do not know how to find my spirit here and so I must leave. I will leave my horse and fine armour, leave my friends and their merry games, leave your hall and your love for me. I will travel across this island we call home and try to find the thing that is missing from me.”

And taking only a bowl made of ash wood, a cloak made of wool, and a tunic made of linen, Adstock left his father’s hall and his mother’s embrace and went to search for that which could make his spirit feel whole.

2.

Adstock walked about the lands to the south, the east, the north and the west. He scooped water from streams to drink from the bowl, wrapped the cloak around him to keep off the rain, and at night he spread his tunic on the ground and slept on it. He spoke to old people, young people, the wise, and the insane. Nothing he saw or did could fill his heart with spirit. Nothing anyone could say to him could make him feel complete. His thoughts and feelings sank deeper and deeper inside him, and he walked further and further, into the valleys, through the woods, across the fields, and along the rivers. He walked all the lands the Saxons now call theirs and then he walked up into the hills of the west.

Adstock rested one cold night in a clearing among the trees on a hill on which are found three types of stone. This is the hill on which we live now, my child. But there was no village here then, no church, no well. Although there were berries, leaves and roots to quash his hunger, there was no water on the hill. With nothing to drink and, desiring sleep to mask his thirst, Adstock lay down upon a slab of slate. Almost as soon as he closed his eyes, he awoke again to find a young girl standing beside him. She was dressed in a tunic of green wool and her feet were bare.

“Who are you?” asked Adstock.

The girl did not answer his question but said, “Please, give me your bowl made of ash wood.”

“But I will have nothing to drink from.” said Adstock.

“You have nothing to drink now. Please give me your bowl made of ash wood and I will repay you.”

The child held Adstock’s gaze and he could not help himself but to give her the bowl. She said nothing more and walked away into the trees.

Adstock closed his eyes again, and woke in the morning to the joyful sounds of running water. Beside him a spring had arisen from between the rocks and filled a pool from which the sweet waters spilled over, streaming down the stony steps of the hillside. Adstock drank from the pool and sat wondering where the girl and the spring had come from.

Night soon came again, as night will. A fine rain started to drizzle across the hill, soon becoming more insistent. Adstock looked for shelter. Near the newly formed well, he found a scattered cairn of broken limestone. He arranged some of the stones into a low wall and crouched beside it, pulling his cloak over him as a blanket against the chill weather. He closed his eyes, but no sooner had he done so than he opened them to see a young woman standing beside him. She wore a dress of blue wool and there were soft leather shoes on her feet.

“Who are you?” asked Adstock.

The woman did not answer his question but said, “Please, give me your cloak made of wool.”

“But I will have nothing to shelter me,” said Adstock.

“You have nothing to shelter you now. Please give me your cloak of wool and I will repay you.”

The maiden kept looking at Adstock, and he could not do anything but give her the cloak. She said nothing more and walked away into the trees.

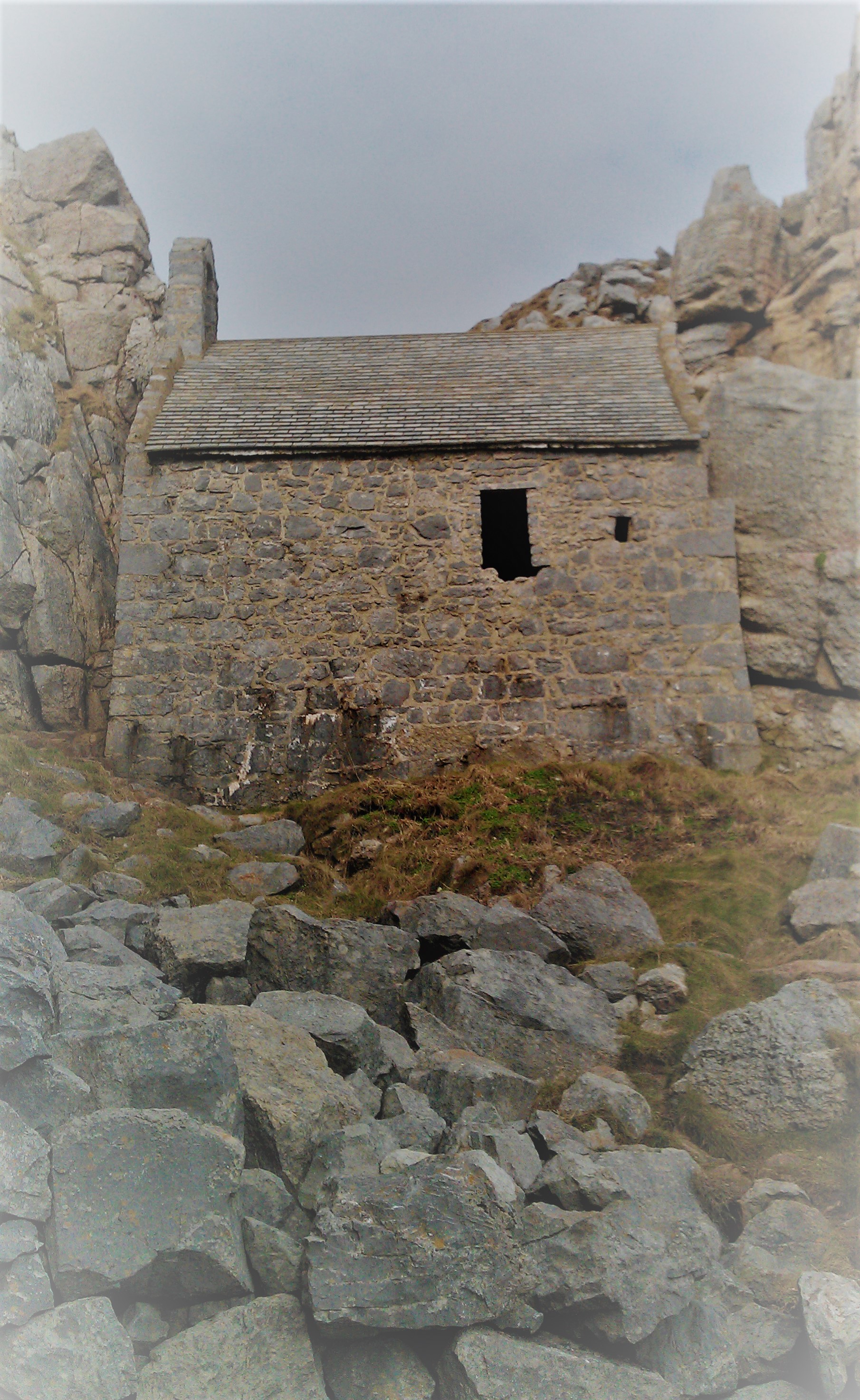

Adstock closed his eyes again and woke later, in the sunshine of a new morning. The light was coming through the window of a little hut built of limestone, in which he now lay. Adstock looked up at the thatch of the roof over him and wondered where the dwelling had come from.

During the day, Adstock marvelled at the exacting construction of the little building’s walls. They were built without mortar, yet the stones were so perfectly matched that not a single gap allowed the wind to whistle through, as our field walls are built today. He examined how tightly staked the reeds of the thatch were. Thick and well-bound, no rain could penetrate the roof, as the roofs of our houses are built today.

With the herbs and fruits amongst the trees to feed him, the spring to quench his thirst and the hut to shelter him, Adstock found the hill very agreeable to stay upon. But still the young man’s spirit longed for something else that he had not yet found and he could not define.

Eventually the night closed in, as it does after every day. Adstock’s thoughts turned to sleep, and he looked at the bare stone floor of the cell. From outside, on the hill, he fetched one of the small boulders of millstone grit, rounded and smoothed, perhaps by the waters of the Flood. This rock would make a pillow for him and his tunic of linen would be his sheet upon the floor.

Almost as soon as he had lain down on this hard bed and closed his eyes, Adstock awoke again, to find an old woman standing beside him. She wore a shawl of red wool over her shoulders and head. On her feet were wooden clogs.

“Who are you?” asked Adstock.

Like the girl and the woman before her, the crone did not answer his question, but said, “Please, give me your tunic of linen.”

“But I will have nothing to wear.” said Adstock.

“You are already naked now. Please give me your tunic of linen and I will repay you.”

The old woman looked patiently at Adstock, and he willingly gave her the tunic. She said nothing more but walked away, out of the hut and into the trees.

Adstock closed his eyes again. When he awoke in the morning, he was dressed in a beautiful purple robe of soft cotton. In place of the rounded and smoothed rock that had been his pillow lay a Bible, and as Adstock turned its pages in wonder and read its tales, his heart was filled with its spirit, and he was complete.

3.

Adstock lived on the hill made of three types of stone for many months, drinking from the spring, sleeping in the little hut and telling anyone who visited him stories from his Bible. They came from far and wide to listen to Adstock, and the young man’s stories caused them to forget their old ways. They laid down their tools on Sundays and kept the day for prayer. They put away their weapons and they stopped fighting each other and they stopped fighting us.

News of this last act reached the thanes and they worried that men would no longer fight in the militias. The thanes spoke to the earls and they in turn worried that men would no longer fight in the armies. The earls spoke to the King and Whaddon worried that men would no longer fight against the neighbouring kings, that he would not have the honour of leading them well in battle and that he would not further increase his lands.

Whaddon sent his advisors to talk to Adstock. When they returned to the king, they said that the Christian man only forbade fighting against others of your own people; it was fine to carry on defending against those who threatened the kingdom. Whaddon was comforted by this and allowed Adstock to carry on living on the hill, telling his Bible stories. However, the king continued to follow the old ways. He did not rest on Sundays, and he did not put away his weapons, but he allowed those who wished to do so, to do so in peace.

But Adstock’s parents were not comforted. They believed that their eldest son had brought shame on their hall.

“He drinks water from a spring,” they said.

“He lives in a bare stone hut,” they complained.

“He has abandoned the old ways,” they wailed. “We must bring him back to the family and to the hall. He must become one of us again.”

And so Adstock’s father called a young boy of the hall to him and said “Go and fetch my son. Tell him he is ordered home, to drink mead with his father and his thanes.”

And the boy rode his pony to the hill made of three types of stone and walked up to the stone building.

“Come out, Adstock, I have a message from your father,” said the boy, boldly.

Adstock came to the smooth slate threshold of the little dwelling and said, “What is the message from my father?”

The boy replied, “You are to return to his hall and drink mead with him and his thanes.”

“No,” said Adstock firmly, “I am staying here in God’s grace.”

The boy was not happy with this reply. He knew that there would be trouble back at the hall when he delivered it. In his anger at his failure to complete the task given to him, he struck at Adstock with his hand and slapped him across the face. Adstock said nothing and walked back into the hut.

When the boy returned to the earl’s hall, he reported that Adstock had refused his father’s order. The earl was very angry, as the boy had predicted, and he had the boy whipped. Then he called one of the young men with whom Adstock used to ride and hunt. He said to the young man, “Go and fetch my son. Tell him he is ordered home, to hunt boars with his father and his thanes.”

The young man saddled his mare, rode to the hill made of three types of stone and walked up to the stone building.

“Come out Adstock, I have a message from your father,” called the young man, commandingly.

Adstock came out onto the path of broken limestone in front of his home and said, “What is the message from my father?”

The man replied, “You are to return to his hall and hunt boars with him and his thanes.”

“No,” said Adstock firmly, “I am staying here in God’s grace.”

The young man was not happy with this reply. He could picture the earl’s face when he delivered it and he knew what had happened to the boy who had been here before him. In his anger at the failure of his mission, he struck at Adstock with his horse whip, which left a red welt across the Christian’s face. Adstock said nothing and walked back into the hut.

When the young man returned to the hall, he told the earl that Adstock had refused his father’s order. The earl was very angry, as the young man had predicted, and he had the man whipped. Now the earl resolved to do the job himself.

“No one can be trusted to do my bidding so I will go and fetch my son. I will order him home, to live in my hall with his father and his thanes.”

And mounting his warhorse, he rode to the hill made of three types of stone and kept riding right up to the stone building.

“Come out Adstock, and answer to your father,” bellowed the earl, angrily.

Adstock came out of the building, stood next to a large boulder of millstone grit, and said,

“What is your message, father?”

The earl replied, “You are to return to the hall and take your place with me and my thanes, to be my son and to lead my people when I have passed on.”

“No,” said Adstock firmly, “I am staying here in God’s grace. I have lived in your beautiful hall, I have enjoyed the companionship of your thanes, I have fought in your battles. Yet my heart was empty and unsatisfied. Here on this hill are simple things that are greater to me than all the riches you have and only here can my spirit be complete.”

The earl was outraged to hear his paternal authority to be denied, his hall denigrated below the stone hovel, and his thanes reduced to worth less than a book of stories. Drawing his sword, he commanded his son again: “You are to return to the hall and take your place with me and my thanes, to be my son and to lead my people when I have passed on.”

“No,” said Adstock firmly, “I am staying here, in God’s grace.” And he began to sing a hymn in praise of his new spirit.

The earl could take no more of this filial insolence and swung his sword. Adstock’s head was sliced cleanly from his shoulders, but he carried on singing his hymn. His head fell onto the boulder of millstone grit, bounced from it, and rolled away, but still he carried on singing his hymn. His head rolled into the well into which the spring flowed and there it floated, Adstock’s face raised to Heaven and still singing his hymn.

The earl stared in horror. “What have I done?” he wailed, “I have killed my son.” He heard the head was still singing and he was aghast at what this miracle showed. “I have killed a holy man.” he cried. And he listened to the words of the hymn and fell to his knees, declaring, “I have denied his spirit and yet it has shown itself to be stronger than that of the warrior in me.”

For three days Adstock’s head floated in the pool and sang hymns while the earl wailed and wept, tore off his fine clothes, and bent his sword in the rocks. Our people from this country, the Saxons from the lands they called theirs, the thanes of the hall, and the family of the earl gathered together on the hill made of three types of stone, and Adstock’s head spoke a sermon to them all. Then he said, “I go now to my God, I give to him the spirit I have found. Take my head from this well, wrap it in my robe, and bury it beneath the floor of the hut. Make the building your church, remember my name, and seek that which delights your spirit.” And with that the head closed his eyes and stopped his singing.

The people did as Adstock had asked, and when they had buried his sainted head, the earl renounced his title and retreated further up the hill to live in a crude shelter built of rocks, where he spent his days in prayer, until he died. The young man who had struck Adstock with the whip stayed in the little church and was for many years its priest, until he died. The boy who had slapped Adstock went on a pilgrimage to Rome, where the pope named him bishop in the kingdom of Whaddon, to which he returned and served, until he died. Adstock’s mother founded an abbey of nuns in place of the hall that she and her husband had ruled, and when the nuns dined, she always seated a girl, a maiden, and an old woman at the head table and served them herself, until she died. And our people, we endured as always, and we moved to the hill and built our village around the church. From here we keep watch on the border with the lands the Saxons now call theirs.

The thanes, now without a hall but with hearts filled with spirit, went to the court of King Whaddon, where they related the whole tale. And Whaddon delighted in the story and had it told to him often. He gave the earl’s lands to the abbey of nuns. He gave the priest of the little church a stipend for life. He gave the boy-bishop a place at his table. And because of that, although people will never consider him a great king, they will always remember him as a good king.